Teaching frameworks and models

Theoretical frameworks and models provide a foundation and approaches for designing learning to enhance teaching outcomes.

Constructive alignment

What is it?

Constructive alignment is a term coined by John Biggs (1996). It refers to the idea that learning activities, desired learning outcomes, and assessment activities can all be ‘aligned’ or oriented to complement rather than conflict. The idea behind constructive alignment is to assess students on the learning outcomes and skills they have developed during a course. In addition, in a constructively aligned course, the learner is shepherded into learning the desired outcomes and skills, so they have the best chance of success when assessed. This alignment also reduces the amount of time students spend doing peripheral or irrelevant work that will not be assessed.

The ‘constructive’ aspect refers to what the learner does, which is to construct meaning through relevant learning activities. The ‘alignment’ aspect refers to what the teacher does, which is to set up a learning environment that supports the learning activities appropriate to achieving the desired learning outcomes. The key is that the teaching methods used and the assessment tasks align with the learning activities assumed in the intended outcomes.

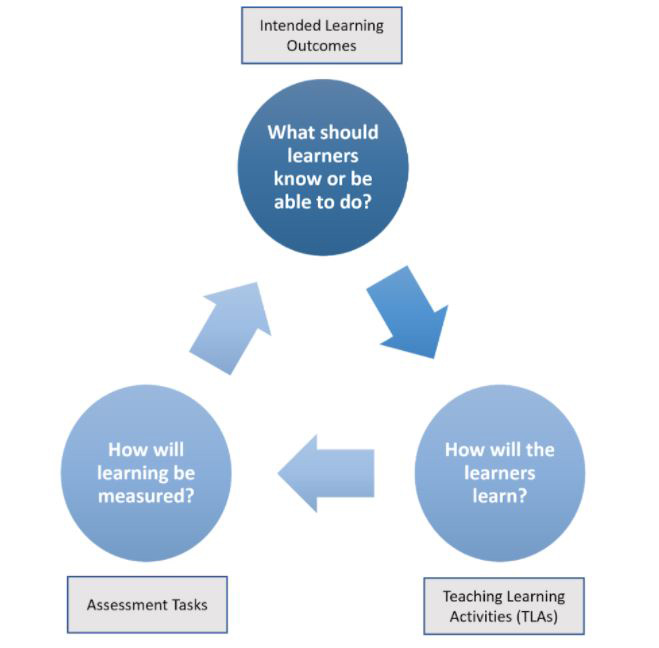

The key elements of a constructive alignment in the design process are:

- Intended learning outcomes (also known as ‘learning outcomes’ or sometimes ‘learning objectives’).

- Activities (what you want the learner to be able to do and achieve to meet the learning outcomes).

- Assessment that is matched to the learning outcomes and the learning activities to show evidence learning outcomes have been attained.

The alignment of these three elements will ensure the course of study flows well, and the student experience will be one of cohesion between what they are expected to learn, the learning activities they undertake and the assessment used to determine their progress.

Why use it?

Ensuring alignment means that students assume a deeper approach to their learning when they are trapped in a “web of consistency” (Biggs, 1999). For example, if a learning outcome aims for students to develop communication skills, you will need to align it with activities to practice those skills, and assessment tasks to demonstrate they have met the intended outcome. This alignment could be through oral presentations, video assignments, or group work where the skills to be assessed are explicitly taught rather than assumed. Shuell (1986) also emphasises the importance of focusing on what the learner does:“Without taking away from the important role played by the teacher, it is helpful to remember that what the student does is actually more important in determining what is learned than what the teacher does. (p.429)”.

How to use it?

Learning outcomes can drive your design of the learning experiences for your students, but some educators prefer to begin with assessment. Ultimately, it does not matter where the design point starts, as long as the elements have a logical connection.

While constructive alignment can be applied to any mode of teaching, it is particularly important when designing blended environments to ensure the online and face-to-face components complement one another and make sense to the learner (Boud and Prosser, 2002).

The following diagram presents a simple way to consider the link between the learning outcomes, assessment tasks and activities.

Source: Adapted from Biggs (2003)

You may find it helpful to begin by drawing up a table to visualise the alignment within your course.

- Write your course learning outcome.

- Identify the assessment the students will undertake to prove they have met that outcome.

- Create a list of the learning experiences and activities that will help students succeed in meeting assessment requirements.

Here is an example:

| Course learning outcomes | Assessment (How the assessment measures the learning outcomes) | Learning experiences and activities to enable learners to meet the assessment requirements |

|---|---|---|

|

Students will be able to explain how constructive alignment enhances student learning and design a course using the principles of constructive alignment. |

Students examine and analyse course learning outcomes and develop: a. aligned assessment tasks to meet the content and level of thinking of the learning outcomes, and b. teaching and learning experiences that students will engage in to achieve the learning outcomes. |

Students will learn about constructive alignment through:

|

Find out more

Aligning Teaching for Constructing Learning (Biggs, 2003) https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/aligning-teaching-constructing-learning

Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher education, 32(3), 347-364.

Biggs, J. (1999) Teaching for Quality Learning at University. Buckingham: Open University Press

Biggs, J. (2003) Teaching for Quality Learning at University (2nd ed.). Buckingham: SRHE and OUP.

Boud, D and Prosser, M. (2002) Appraising new technologies for learning: a framework for development, Educational Media International, 39, 3,& 4, 237-245. ISSN 0952-3987

Shuell, T. J. (1986). Cognitive conceptions of learning. Review of Educational Research, 56(4), 411-436. doi: 10.3102/00346543056004411

Backward curriculum design

What is it?

Backward curriculum design is a framework for planning and designing effective, inclusive and aligned courses within our programs. It is a way of thinking purposefully about planning curricula and can is used for course and program planning. The Backwards Curriculum Design process ensures that more students in your course are more likely to understand what you are asking them to learn. It does this through steering clear of ‘coverage-focused’ or ‘activity-focused’ teaching and encourages us towards a purposeful, inquiry-driven, and engaging curriculum. The framework is provided in 'Understanding by Design (UbD)' (Wiggins and McTighe).

Why use it?

The deliberate use of Backward Curriculum Design results in better curriculum alignment from clearly defined course goals to more appropriate learning activities and assessments.

The key benefits to students are:

- clear alignment through the course, from learning objectives, through to assessment, through to learning activities,

- a focus on developing and deepening understanding of important ideas, and

- a focus on the intellectual impact on all students, not just the highly able.

A well-aligned and intentionally designed course will help students understand the purpose of the course, the benefits of the assessment and the value of the learning activities. This will improve student engagement. If the course is intentionally positioned within a program, with clear alignment to the intended program outcomes, then students are more likely to appreciate the value of the course to their learning.

How to use it?

When designing a course, we begin with imagining the end result - the student’s knowledge, understanding and skills who has completed the course. With the end goal in mind, we work backwards through the course to design meaningful and goals-driven learning.

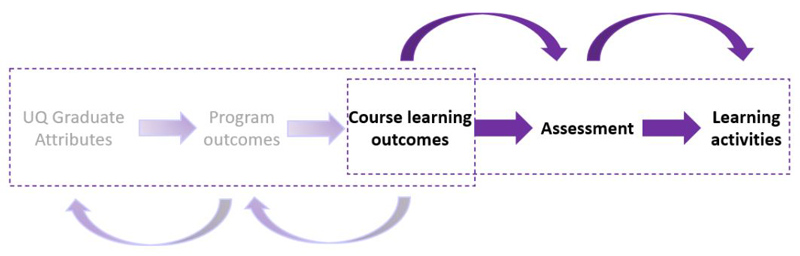

- Craft your course learning outcomes. Identify your desired results – what should students know, understand and be able to do? What enduring understandings are desired? Which skills do we want students to develop?

- Ensure your course learning outcomes map to your program outcomes and the UQ Graduate Attributes.

- Design the course assessment. Determine acceptable evidence – how will you know if students have achieved the desired result? What will we accept as evidence of student understanding and proficiency? Consider upfront how you will determine if students have achieved the learning outcomes.

- Plan your learning activities. Start by planning learning experiences and instruction – what enabling knowledge and skills will students need to perform effectively and achieve desired results? What activities will best allow them to practice skills and accomplish performance goals?

Find out more

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2011). The Understanding by Design Guide to Creating High-Quality Units. Alexandria: ASCD.

Wiggins, G., McTighe, J., & Thomson Gale. (2005). Understanding by design (Expanded 2nd ed., Gale virtual reference library). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Conversational framework

What is it?

The conversational framework was described by Laurillard in 2002, and it involves putting the student in the centre of the learning process. The Conversational Framework embraces the notion that teaching is a dialogue and shows what it takes to learn, using the ideas of instructionism, social learning, constructionism, and collaborative learning.

The conversational framework emphasises interactions between teachers, learners, peers and the learning environment at both the conceptual and practice level.

Laurillard identified six types of learning activities: acquisition, practice, discussion, inquiry, collaboration and production in Teaching as a design science (2012) and mapped these to the conversational framework.

Source: adapted from Laurillard (2002)

Why use it?

The conversational framework provides a model to consider and design interaction in your courses. Having this framework for consideration is particularly powerful when learning experiences differ across modes (e.g. online or face-to-face) to ensure learners are experiencing a mix of learning activities and interactions likely to achieve the learning outcomes.

How to use it?

In designing a course or sequence of activities, consider learning activity types that are best suited for your students. Then reflect on the balance of activities and interactions planned for your students. Will this create the experience and outcomes you want to achieve in your teaching?

In reflecting on your teaching, consider the experiences created. Were the planned interactions effective? Did the activities each work? Was the balance of activity types, suitable for the context?

Video: Conversational framework - Diana Laurillard, University College London [YouTube, 2m 38s]

Find out more

Laurillard, D. (2013). Teaching as a design science: Building pedagogical patterns for learning and technology. Routledge.

Laurillard, D. (2002). Rethinking university teaching: A conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies. Routledge.

Need help?

ITaLI offers personalised support services across various areas including using learning frameworks and models to inform the design of curriculum, learning activities and assessment.